Marek WasilewskiExcavation curator: Magdalena Radomska

10–30.03.2022

Magdalena Radomska

THE ARSENAL OF SYNCHRONOUS COLLECTIVES – MAREK WASILEWSKI’S EXCAVATION AND FORMS OF RESISTANCE

The concept of Marek Wasilewski’s exhibition, Excavation, was created during the modernisation Arsenał Municipal Gallery building in Poznań, which Wasilewski has been director of since 2017. The exhibition consists of four works, three of which – including the titular Excavation – were created as documentation of the discoveries made by the artist during the removal of contents from a modernist building designed in Poznań’s Old Market Square in 1954–1962 by a team of architects – Jan Cieśliński, Zygmunt Lutomski and Regina Pawulanka. Excavation, a seemingly simple work, which consists of a set of photographs taken by Wasilewski in an empty building, is readable through the prism of institutional archaeology, as well as its history and what can be called the archaeology of the gaze.

Wasilewski’s exhibition at the SKALA gallery in Poznań is interesting as an artistic commentary on the insufficiently developed problem of the branch offices of the Central Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions, which functioned from the beginning of the 1950s. The Central Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions was an institution established by the Ministry of Culture and Art at the request of the Association of Polish Artists and Designers (APAD) in order to promote contemporary artistic works and state supervision over contemporary art and artistic life in the Polish People’s Republic. This included the roots of the still-functioning network of Polish institutions of contemporary art. Excavation, Exhibits and Plein-airs reach for material traces and artefacts of the history of the institution, but also the history of the building itself as a material carrier of social, economic and gender relations.

Among the series of photographs that make up Excavation, there are those that document the material synchronicity of the various stages of the Gallery’s functioning, reducing them to – literally – a common wall surface which bears the traces of several interior renovations by revealing fragments of the unpainted wall – hidden by the objects which were there at that time. Wasilewski does not succumb to the temptation to reduce the frame of the image he photographed to the smooth surface of the wall, and thus – a complex, material message. Nor does he reduce it to a distilled and comfortable form, cleared of rubbish and debris lying on the floor, disrupting the potential, simplified message, according to which even the tedious cleaning of the Gallery of artistic objects would not allow it to reveal itself as anything other than an art space – due to the visual tension of the painted wall and the tradition of the modernist image. Such a procedure would only succumb to the oppressive tradition of formal analysis, falling into its traps of elitism, dependence on institutions, hierarchy, etc. It would be like the striptease described by Roland Barthes, where nudity never comes to the fore, but an act that functions as the last of the costumes to be stripped off1.

Wasilewski operates – literally and figuratively – with a wider frame, in a way that allows a material analysis to speak, taking into account labour relations, hierarchy, the economic conditions of the functioning of institutions, but also – by exposing the usually invisible work of workers, whose task is to constantly reconstruct the white cube as a distilled space – it is cleansed not only from body and context (as O’Doherty claims)2, but also from social, economic and labour relations. In the work of Marek Wasilewski, they are visible in the form of savings during renovations, but also in the inviolability of the interior fittings, which, after all, reflect the working relations, hierarchy, etc. prevailing in it, which appear as existing.

It is worth mentioning that when the space of the then branch office of the Central Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions was put into use in 1962, the famous text of the Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman, On the Characteristics of Total Institutions, was already in circulation. This was the text in which Goffman formulated the famous theory of a “total institution”3, a starting point for institutional archaeology. Although the text referred to institutions of aid, seclusion, protection, or organised work – such as orphanages, hospitals, monasteries, prisons, boarding schools and labour camps – it seems that his framework can be successfully applied to institutions that structured the then artistic life of the branch offices of the Central Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions, which constituted the ersatz of the workplace, but also which were burdened – as Piotr Piotrowski wrote – by a strong attachment to the modernist image, resulting in a reluctance to accept critical perspectives4. Thus, contrary to their destiny as meeting places for artists associated in trade unions, they also functioned as places of seclusion, where the elite longings for the model museum-temple could be realised5.

The photographs in Excavation also subtly evoke the models of institutional criticism functioning in Polish art, such as Edward Krasiński’s project at the Foksal Gallery in Warsaw entitled Winter Assemblage, which was critical of the institution of the gallery and in which Krasiński laid a cable out of the Gallery, the end of which had to be found by visitors to the Gallery, outside its walls. In Wasilewski’s work, it is a blue hose, a tool not of the artist, but of the workers renovating the Gallery. The artist does not appropriate it as a tool of his work, he does not pick it up, he leaves it – just like the geometric stains of paint on the wall – in the hands of the workers. He does not overly process the photography, he does not care about isolating the motive and showing it in its material, non-formal form.

The black fragment of the wall appearing in the photographs is given a similar status; it becomes a pretext for problematising the educational dimension of art – recalling the works of Jarosław Kozłowski or Joseph Beuys through the launch of the archaeology of gaze, and its revolutionary aspect – by referring to the works of Malevich. However, it retains its material dimension. The white wall of the Gallery shows the work of the workers rather than hides it. Wasilewski’s photographs document the moment when the work of the labourers in the Gallery does not become a customary figure of alienation. It is not undertaken in order to restore the white cube and thus maintain its own invisibility in this institutional system – semantic and visual. On the contrary – it is about excavation – gouging, dirtying, making holes.

This is reminiscent of the work of the Hungarian artist Tamas Szentjóby, who, while preparing his own retrospective at the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, opposed the renovation of the exhibition space after the previous exhibition and displayed his works against dirty, leaky walls, which meant that they were juxtaposed with the work of the Museum workers. Wasilewski’s photographs depicting shoe prints on the floor are a kind of contemporary realism in the genre of Caillebotte’s The floor scrapers – not only do they not favour the trace left by the artist over the traces of workers, but they make them indistinguishable.

It should be added here that the work of Wasilewski the artist, is framed in a way that gives it credibility by the work of Wasilewski the director. The programme of the Arsenal Gallery, co-run by Zofia nierodzińska, is very far from the paradigmatic nature of formal analysis. It takes into account various forms of art and activism, does not favour art as a privileged form of work, does not point to it as the domain of artists and does not isolate it from the political and social, economic or gender context. Finally, it does not create favourable conditions for the alienation of artistic work.

Shortly after Marek Wasilewski assumed the position of director of the Gallery in 2017, his exhibition Excavation seemed to contradict his organisation of: “cleaning the Arsenal, chasing away evil spirits and airing the Gallery”, which was to constitute a symbolic turning point in its functioning according to the rules imposed by its previous director – Piotr Bernatowicz, who had displayed portraits of the Cursed Soldiers on the facade of the building. Although Wasilewski’s aim to attempt a clear break from the right-wing, pro-nationalist narrative of the Gallery under Bernatowicz, it was also a controversial subject in terms of labour rights of the part of Bernatowicz’s support team, who refused to get involved in it. Excavation is a movement in the opposite direction – although it arose during the process of cleaning the Gallery, its author is interested not in the diachronic progress, but in the materialised synchronicity of the Gallery’s history. Wasilewski’s work Happiness was similar in this respect; it was created the same year the financial crisis broke, reinterpreted 1989 and the systemic transformation as an apparently linear process – identical to the process of progress, capitalisation and privatisation from the perspective of the economic crisis and the crisis of capitalism.

Wasilewski’s work shown at the exhibition also dealt with the concept of the collective, as perceived by Bruno Latour in a text whose title echoes the Excavation exhibition – We have never been modern. Latour uses the concept of the collective and “describes humans and nonhumans”, and points to the fact that the term “society” is only a part of it6. It is visible in the artist’s photographs showing the contact between the wall and the floor in the renovated gallery, which – due to their format and structure of division – remain in tension with the Polish flag. Here its lower portion materialises not only as an object – part of the floor, but fragments of mould, dirt and other non-human collectives. Wasilewski not only departs from the concept of the nation towards the concept of a social collective; he also shows the authenticity of nature and culture, as does the Estonian artist Tanel Rander’s Decolonise This (2012), which presents a Friedrichian wanderer against the background of the Estonian landscape (divided similarly to the Estonian flag).

This artistic direction is again consistent with the activities of Marek Wasilewski as director – it is worth mentioning here, for example, Monika Bakke’s excellent Refugia: The Survival of Urban Transspecies Communities project at the Arsenal Gallery. Bakke’s project was crowned with an exhibition and a series of events indicating that the Arsenal Gallery cares about its location not only in the political, social and economic context, but also in the context of the biodiversity of the environment in which it consciously functions.

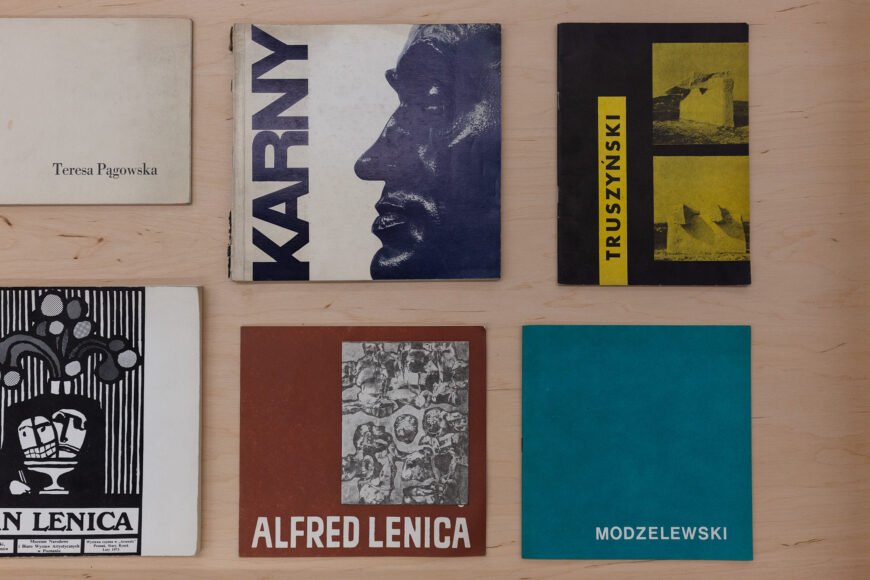

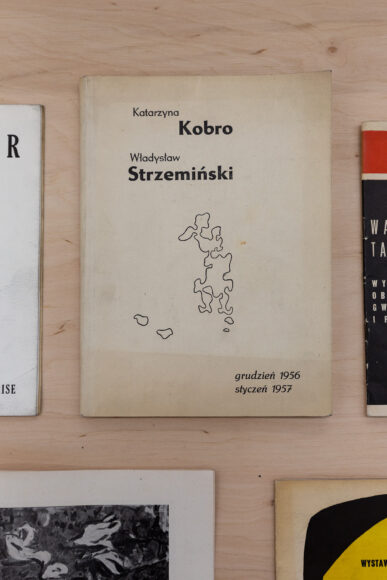

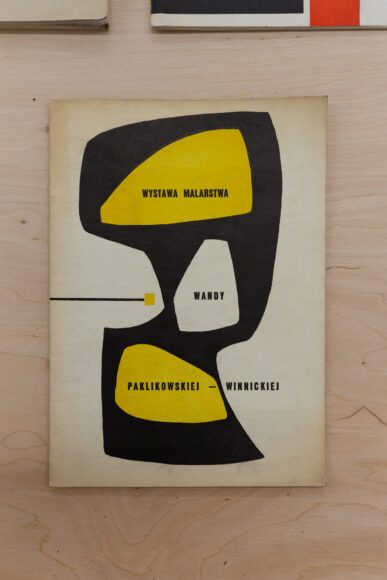

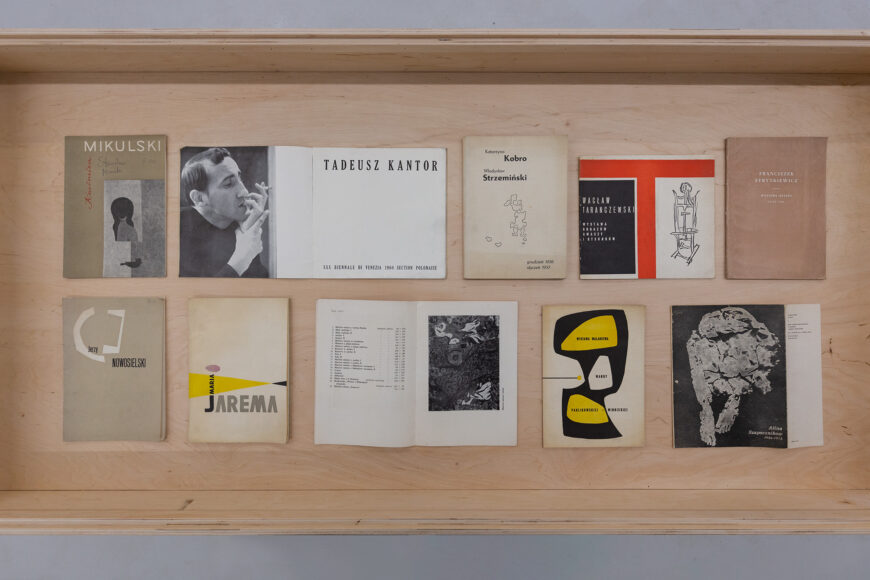

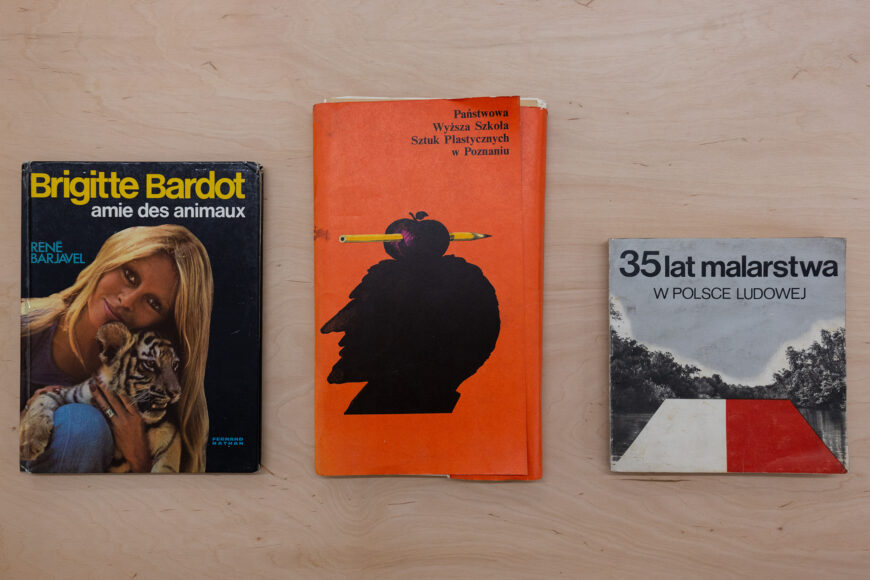

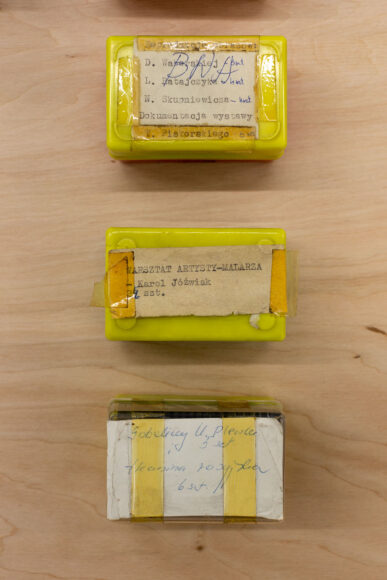

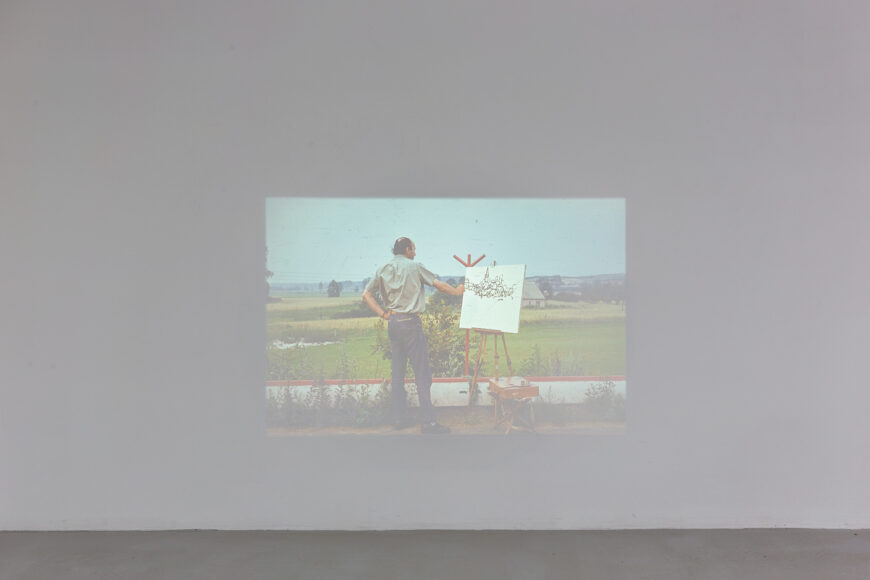

Wasilewski’s exhibition at SKALA is therefore an archaeology, the subject of interest of which is collectives understood in different ways. Although the photographs also show the actual “Excavation” intended to reveal the structure of the building during restoration works, and the fact that the Gallery’s modernist building was built on the existing foundations of historical buildings, Wasilewski is mainly interested in collectives of things not catalogued and merging into the fabric of the building. These are inconspicuous catalogues displayed in the exhibition in conventional display cases as Exhibits, and the slides depicting Plein-airs taken out from the backs of drawers (presumably by members of the Association of Polish Artists and Designers).

The juxtaposition of these two works in the exhibition space is particularly clear – it escapes the dualisms of people and their works, the open air and the exhibition space, and creates a completely different field of tension. Contrasted in such a way, the works problematise the matter of this gallery as an arsenal of human and non-human collectives and provoke the question of collective and trade union aspect of artistic life, or the state structures of its functioning (Plein-airs). But they also demand answers about the oppressiveness of the concept of modernity and its paradigmatic constructs (Exhibits), written about by, for example, Latour and Walter Mignolo7.

The Plein-airs, however, also introduce lost materiality into the exhibition space: items from communist times, such as clothes and busses. They make it possible to situate the notions of new materialism, which influence Wasilewski’s works, in the context of historical materialism and socialist reality. A good example of this is the slide showing a bus used during the plein-airs, not only a kind of artefact but also – similarly to the works of Krzysztof Wodiczko and Movement Academy from the 1970s (Vehicle from 1973 and Bus 2 from 1975) – a vehicle of historical materialism and modernity, moving along the axis of progress and towards the future. The use of the conventional method of displaying Exhibits in showcases is synonymous with the gesture of musealising the narrative of modernism.

Wasilewski is interested not in modernist landscapes, but in social landscapes and the hybrid nature of the notion of plein-air, which remains outside the gallery space, but which at the same time functions in the context of the constructed, oppressive and ossified narrative of modernist landscapes and, more broadly, images. The showcases display catalogues of various recognised artists – Kantor, Kobro, Hasior, Nowosielski and Szapocznikow, who in this configuration both succumb to and resist the oppressive narrative of modernity, but not in a conventional way practiced during the formal analysis of specific works and artists, but as collectives of subjects. Squeezed under the wardrobe or behind it, or even overlooked – these material objects (similarly to unpainted wall fragments once hidden behind furniture) are figures of resistance8. They are material artefacts which, while unclassified, allow for the synchronous coexistence of contemporary and ancient forms of collectivism and collectives.

Wasilewski’s exhibition topicalises the issues of the APAD-ian identity of the Poznań branch office of the Central Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions at an important historical moment – in which an extreme-right vision of culture is being forced in Poland. Just a few months ago, artists, curators and art historians were united in protest against appointing a conservative, locally known painter Janusz Janowski as the director of the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw. Janowski is associated with the Association of Polish Artists and Designers community and has no experience in running a cultural institution. The appointment happened with the approval of the Association’s committee members but without the participation of trade union representatives at the Zachęta Gallery. These events, similarly to Wasilewski’s exhibition, provoked discussions about trade union aspects of artistic life.

The books displayed in showcases also problematise the concept of the collective in a different way. Covered with non-human life forms, often materially interacting with the works reproduced in them, they are figures of resistance against formal analysis, which is paradigmatic for the institution of modernity. With a peculiar wink to the viewer, the album Brigitte Bardot – Animal Friend from 1976, which is among these figures, provides the exhibition with the context of feminist materialism (for example Donna Haraway’s considerations), but also allows the Gallery’s history to be accounted for in terms of gender equality. Here again it is worth referring to Wasilewski’s policy when running the Gallery. Not only does he respect gender equality in terms of the Gallery’s employees, but also supports projects such as the workshops of the Barcelona-based Gyne Punk collective, who work on issues of corporeality and women’s rights to choose in the context of fertility and motherhood, which are particularly relevant to the current political situation in Poland.

The exhibition culminates in Wasilewski’s work, Earthquake, a set of photographs taken at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, showing cracks in the white walls of the Museum, caused by an earthquake. Another work by Wasilewski, Stones, shown in 2015 at the Kronika Centre for Contemporary Art in Bytom, is also worth mentioning. It took the form of a multi-channel video installation, and featured stones appearing in various places of worship, including Fatima, Jerusalem and Istanbul, and their interaction with pilgrims. However, what draws the viewer’s attention in Wasilewski’s work is the cracking on the stone’s surfaces, similar to that documented by the artist in Zagreb. There is no doubt that it is about unsealing hegemonic narratives concerning either objects of worship or exhibition institutions – but both works also use the notions of nature and culture in a non-dichotomous way, pointing to cracks in their material carrier. In this sense, they are also points of resistance, which arise where matter appears to yield to the forces acting on it.

Earthquake also creates a new interpretive context for Excavation by means of the lines of cracks on the wall of the Zagreb museum and the hose on the floor of the renovated Arsenal Gallery, which have similar functions. These hoses are also a kind of crack in which materialises that which Wasilewski did not manage to appropriate: non-artistic tools of work, which function as forms of resistance to institutionalised space.

Magdalena Radomska

Translation: Aleksandra Sokalska-Bennett

1 R. Barthes, Mitologie, Warszawa 2000, p. 186.

2 B. O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube, The Ideology of the Gallery Space, San Francisco 1999, p.76.

3 E. Goffman, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, new York 1961, pp. 4-12.

4 P. Piotrowski, Awangarda w cieniu Jałty. Sztuka Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 1945-89, Poznań 2005, pp. 185–186.

5 D. Cameron, The Museum, a Temple or the. Forum?, “Curator”, vol. 14/1, 1971, pp. 11–24.

6 B. Latour, Nigdy nie byliśmy nowocześni, Warszawa 2011, p. 14.

7 Cf. Ibidem, p. 17; In. Mignolo, Epistemiczne nieposłuszeństwo i dekolonialna opcja: Manifest, “Konteksty” 2020, no. 4, pp. 15–30.

8 This category is discussed in more detail in the book: April M. Beisaw and James G. Gibb [eds.], The Archaeology of Institutional Life, Alabama 2009, pp. 24–25.