Piotr MachaJesus Was Born 6–4 Years Before Christ 1—14.10.2021

ON PIOTR MACHA’S EXHIBITIONJESUS WAS BORN 6-4 YEARS BEFORE CHRIST

Piotr Macha’s exhibition Jesus Was Born 6-4 Years Before Christ can be seen from different points of view and dimensions in which we operate today. He conveys a multifaceted message; one which is open to complex and intersecting areas of visual culture. Macha can sense the gaps and overlaps –not only in the sense of the breakdown of classical linearity or in the way of conveying the content, but also in the sense of the interpenetration of physical and virtual dimensions, their mutual “haunting”. The title of the exhibition Jesus Was Born 6-4 Years Before Christ signals its contradictory and non-obvious character. Moreover, it is full of ghosts: Mark Fisher is undoubtedly one of the main ones, whose theory is referred to in several places; Jackie Kennedy is another ghost; as is the virtual apparition of Sam Fisher, and so too perhaps the most enigmatic but nonetheless emblematic spirit of Maria Rekowska, whose drawings were found by the artist at the flea market (in the Old Slaughterhouse in Poznań) and are also part of the exhibition.

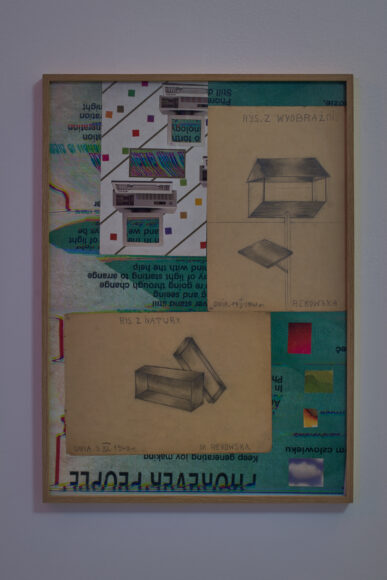

Rekowska draws with a pencil from memory, from imagination and from nature. Regardless of the source, these works are quite similar in terms of form and theme –with the exception of one that is quite abstract and which depicts what could be a plough, an axe or a hook-ended snake, coming out of a pair of trousers. Macha juxtaposes these drawings with his own works, and by using felt-tip pens or Donald Duck bubble gum comics, he evokes nostalgia in the visitors who grew up in the 90s. The artist creates strange, clunky collages that do not hide their component parts from us; we can imagine them broken down into prime factors, element by element; a few drawings, a piece of carbon paper, abstract scraps. They rely and are based, in a nonchalant way, on the recipient’s memory (and their participation in collective memory), their tart sense of humour and the ability to combine incompatible forms into coherent messages. Macha’s collages are a bitter and far-sighted reflection with abjection as the leitmotif. A CD – which is a reference to the cover of Kanye West’s album with the title Yezuus,(and so, significant in this context) – primarily reminds us of the fragile structure of modern memory carriers. Regardless of West’s megalomaniacal tendencies, his legacy, and more broadly, a large part of contemporary cultural heritage is written in the medium and on carriers that are not permanent. CDs, tapes, and disks, even if undamaged, are possibly indecipherable; inhabited by ghosts of data that we do not have, or will soon not have, access to. They work in harmony with Rekowska’s memory, but also reflect on the archaeology of technology, the constant progress of which makes it impossible to access their content, without removing their form. They semi-last and condemn us to refer to our own memory in the end. Tire graveyard (Macha), a cross (!) (Rekowska) are studies not so much from nature, as the latter indicates, but of nature itself –and despite the different times in which they were created (Rekowska’s drawings come from 1940), they are a record of distortions and perspectives, which, apart from the rigid framework, becomes more and more unnatural.

Macha also questions the issues of memory and historical perspective in his loop video showing Jackie Kennedy in a costume, which remains stained to this day and functions in our imagination as one of the most legendary garments in history, and which is stored in a specially constructed, acid-free box in air-conditioned National Archives ( College Park, Maryland). At Caroline Kennedy’s request, it is to remain there until at least 2103. The costume is also perfectly preserved in collective memory; we have seen it in documentary photos, and its reproductions in dozens of films, music videos and comics –all these images are superimposed on each other, are blurred and boiled down to certain generalities; limousine, pink suit, blood and woman on the hood of the car. In Macha’s video, we see pink, blood and Jackie stained with it, though we know it is not her blood, but the blood of President JFK –a belief that stays with us even later, when Jackie is lying, covered in blood and dead on the ground, with a close-up on the gunshot wound to the head. When Macha used to play JFK Reloaded, in which the player has to kill JFK, he always wanted to hit Jackie – he finally succeeds at the exhibition. But at the same time, Macha allows her to be resurrected.

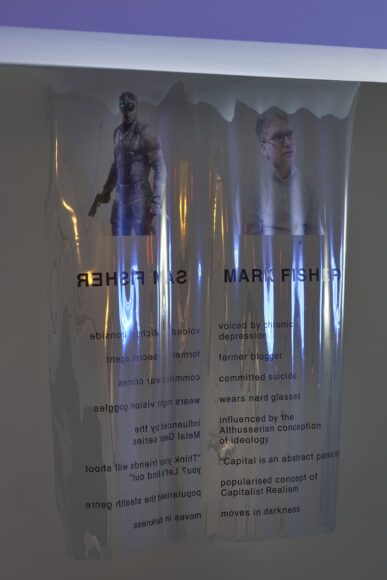

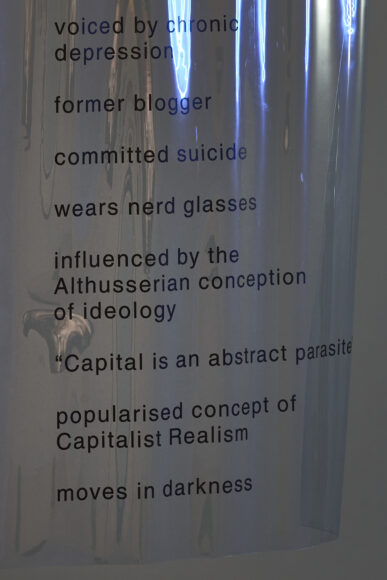

In the spirit of the same omnipotence, he places Sam Fisher, the fictional hero of the Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell series of books and computer games, alongside the writer Mark Fisher; their silhouettes are printed on transparent foil, which acts as a curtain. He sets both characters against each other, in a mirror image: we have to stand on opposite sides of the curtain to read the biographies of both. When reading about Sam, we see Jackie waving at us in the background. When reading about Mark, we can see baseball caps, worn by the artist, hung at equal spaces, which are separated by a casual message sewn with red thread:YOU – HAVE – NO – IDEA. YOU is immersed in a toilet, whose movable flap reveals its contents to us again and again. Looking inside the toilet is reminiscent of Hitchcock’s toilet from his Psycho. Macha shares Hitchcock’s love of the abomination that Žižek writes about inLacrimae rerum– while Hitchcock, however, was censored and was not allowed to reveal the inside of the toilet bowl and its bloody secret, Macha allows the toilet to whisper to us about the ideas gone down the toilet, not hesitating to mention who will sink with them.

Fisher analyses the departure from the modernist challenge of innovating cultural forms in a way that is adequate to contemporary experience in his book Ghosts of My Life, which accurately portrays all our ills, fears and intuitions. Macha places its title between two skeletons on a canvas, which he places against the wall. Fisher writes about the end of time and the lack of a future, about the constant movement that brings us nowhere; Macha’s toilet opens and closes, Jackie gets cleaned up, and despite the fatal shot, she continues to greet us. The lack of a future is understood here not only as the non-alternative nature of neoliberal capitalism in which we operate, but above all as the effects of its impact on culture over the last 30 years. Fisher describes the stagnation of culture, which refreshes past eras, mixes decades and is based on clichés of collective imaginations. The twenty-first century, on the other hand, continues to calcify, constantly satisfying the audience with a correctly prepared dose and combination of nostalgic clichés that soothe the hardly perceptible longing for something that was good, but also what we simply knew. However, as Fisher writes, it is difficult to imagine what such a set of “clichés” and consensus ideas could be like.

Over the last 30 years, the dominant (in the West) model of toilets has changed, which in the context of the discussed exhibition and considerations by Fisher turns out to be significant. In her famous analysis of the lavatories in the novel Fear of flying, Erica Jong describes different toilets: the French model (the contents of which disappear immediately after flushing), the German model (whose contents can be inspected) and the American model (which is a fusion of the previously mentioned models); the content floats but is “elusive”. Today, German toilets have basically fallen out of use, and the cultural circle broadly referred to as the “West” is usually divided by one model of the toilet – the French-American one, which swallows the contents. And this is perhaps the only area of modern Western functioning that is under-recorded, making it essentially a phantom.

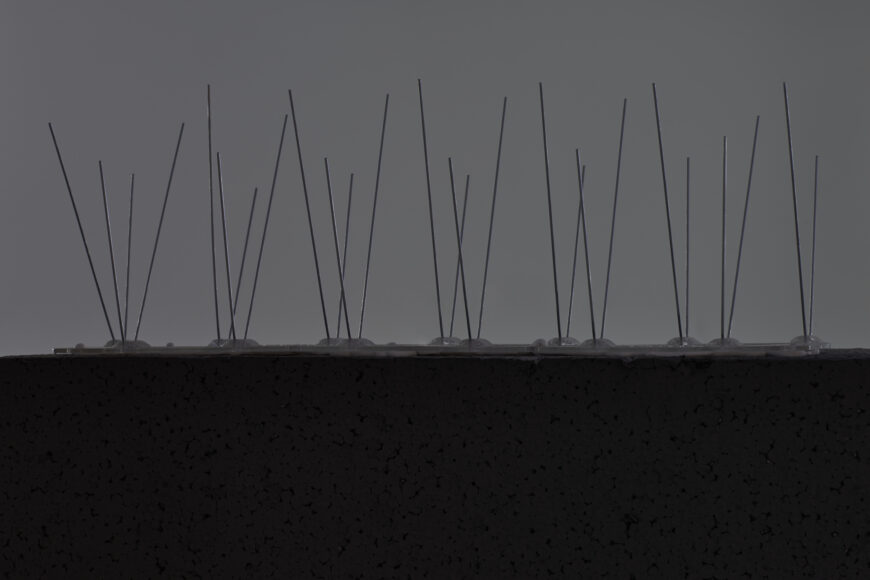

The huge PlayStation logo is also a phantom and resembles a monument topped with spikes protecting against birds. It is immersed in twilight, illuminated in a similar way that city lights illuminate their topography; partially, nonchalantly, inaccurately, randomly. This creates an atmosphere reminiscent of a mixture of Blade Runnerand the Matrix, but also any square in any city that is full of invisible monuments, stone ghosts, nameless and great.

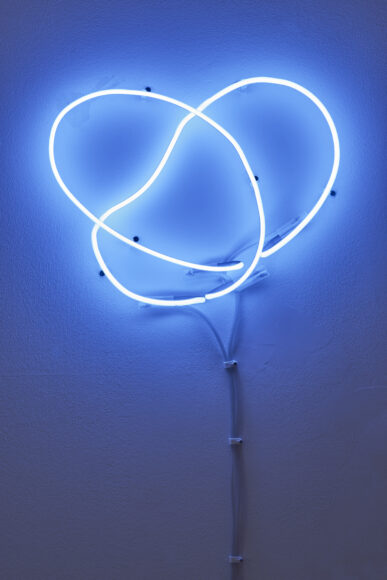

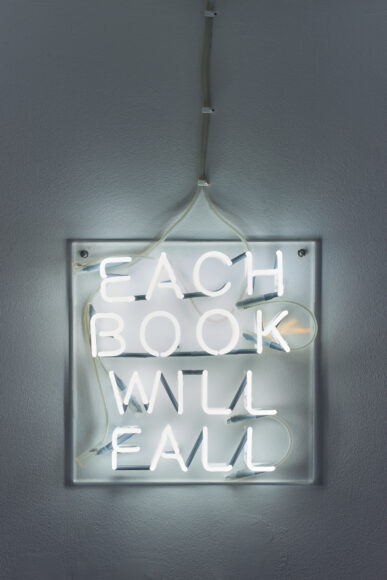

Macha’s neon lights bring to mind an encrypted message; two of them are visual equivalents of the words taketeand maluma, abstract symbols used in an experiment conducted in 1929 by Wolfgang Köhler, in which the subjects were to match the appropriate visual representation to the verbalised words. Most of the participants, regardless of their background, assigned the round-sounding word malumato a rounded shape, and the word taketeto an angular shape. The dual nature of a word is already contained in the form of its visual representation and the corresponding sound, which differ due to the multitude of languages and alphabets. The research suggests that as a species we share this perception of abstract form, at least in the most extreme examples. Mallarme observes that the way words sound do not necessarily correspond to their meaning; annoyingly, for example, joursounds dark, nuit–light[1]. He assigns poetry the task of creating a bond between them and refers to the ancient etymology of words, where these relations were alive. In a similar manner, Macha assigns yellow to the curved form, and blue to the angular one, which is also consistent with the common and intuitive ascribing of colours to shapes. Macha is less concerned with language, but rather negotiates the use of the medium itself –that is, neon and its functions.

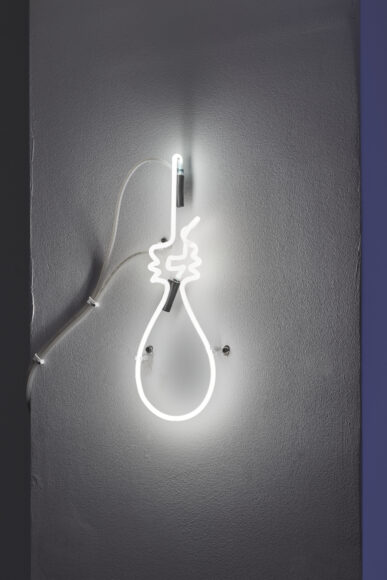

Another neon sign, this time a gallows knot (Fisher died by suicide by hanging in January 2017) is also a Eureka! comic book light bulb. It is, however, not about light; Neon signs do not fulfil their pragmatic or luxurious function in the form of advertisements and signs on city streets, nor do they function as a traditionally catchy exhibition facility, but are instead a critical commentary on these functions. Red paving stones may refer directly to the place of neon in the city topography and they bring to mind problems of urbanisation such as gentrification or evictions. In the context of the art gallery, however, cherishing neon in the same way in which it did so light boxes until recently (because they always “work”), the form of Macha’s neon lights is almost irritating. They are not a catchy text, they demand substantive support from the visitor, they are demanding of the visitor. Time and mental space for intellectual effort to learn about “novelties” are a “commodity” that is missing, and the intensity and precariousness of functioning in late capitalism results in overstimulation and exhaustion, which obviously leaves its mark not only on the recipients of culture, but also on its creators. The problem, therefore, does not exist in experiencing the 21st century itself, but rather in the lack of time to experience it, as Macha reminds us of by placing an inconspicuous wristwatch on the wall, which his partner at that time set for 4.20 and left by his bed; for the duration of the exhibition this alarm goes off in the gallery at 4.20 am. In addition to the time and connotation close to marijuana consumers, the form of the watch itself brings to mind the English verb ‘watch’, which also refers to keeping watch and waking. Fisher writes about a society that cannot cope with history and, over time, longs for form. Perhaps the only forms we are faced with are those created by the needs born of capitalism, such as backpacks/containers delivering food from restaurants for the lowest hourly wage, which are most often immigrants from geographically distant countries, providing cheap labour. Uber Eats bags are an instantly recognisable form, regardless of whether they contain their logo or the inscription Only Sleep. This work, however, is far from the already cliché ready-made; it doesn’t so much capture a visual artefact of contemporary culture (the proverbial Cambell’s soup), but rather is characterised by postcolonial self-awareness. The Only Sleepslogan is, as it were, an admission of guilt – the question remains, what to do with such a feeling of guilt. Macha is a keen observer of the structures we are entangled in within the dominant system. His work does not allow us to forget about the place we occupy in these structures. It is also not a simple and unambiguous critique of specific phenomena or sensationalist visual journalism. If Macha pursues current socio-political events, he inscribes them into a broader discourse; in a sense he gloats over another bleak vision that has been fulfilled: a motif that has already appeared in his work as a phantom, which now becomes a fact. In this way, Macha does not so much summon ghosts, on the contrary, he foretells the phantoms and visions that will haunt the ages and dimensions to come; which we fear whilst also letting them come true.

Ewa Kubiak

When writing the text, I used Mark Fisher’s book “Ghosts of My Life”.

[1]Artur Sandauer, “Samobójstwo Mitrydadesa”[Trans. Mithridates’suicide]

Translation: Aleksandra Sokalska-Bennett

Piotr Macha (born 1982) – a graduate of painting at the University of the Arts in Poznań, where he currently works. In his practice, he combines various media and forms of articulation – from drawing, through curatorial practices, poetry, analogue film, to sound installations. His works have been presented, among others, by theZachęta – National Gallery of Art,Kunstquartier Bethanien Berlin, and the Wrocław Contemporary Museum.