Frederick Kiesler, Piotr ŁakomyThrough The Ribs 9.1—14.2.2020

Dorota Michalska, A Contaminated Landscape: Piotr Łakomy’s Post-Objects

The exhibition Through the Ribs aims to illustrate the connections between the works of Piotr Łakomy and the artistic practice of the Austrian-born American architect Frederick Kiesler. The focal point of the show is the idea of the Endless House – Kiesler’s unrealized architectural project that embodied his reflections both on historic time and geological processes of a cosmic scale. Over the years, a number of interpretations of the project have emerged which, much like accumulating layers of dust and soot, have obscured the idea’s multifaceted and often ambivalent meanings. The goal of Łakomy’s artistic investigation is to bring to light and explore those forgotten layers. What gradually emerges from the show is an entirely different image of Kiesler’s most famous project: that of a house as an underground shelter with infinitely looping corridors and shadowy spaces; a house as a place located on the outskirts of some unnamed catastrophe. This interpretation of the artistic practice of the architect also offers a different perspective on the works of Łakomy himself, bringing out aspects that previously have been overlooked.

I.

Kiesler’s archive in Vienna includes an article about a fatal accident that occurred in a nuclear laboratory in Los Alamos in June 1946. During a routine experiment, there was a leakage of radioactive material: the attending scientists felt a sensation of warmth and witnessed a slowly spreading blue glow. A few days later, two of them were dead. Contact with radioactive material leads to accelerated degradation of human DNA. As a result, the genetic code disintegrates into a pool of basic proteins. One of the scientists from Los Alamos stated that he had felt as if he had been witnessing “the process of reverse creation”: a violent breakdown of complex biochemical structures into basic elements.

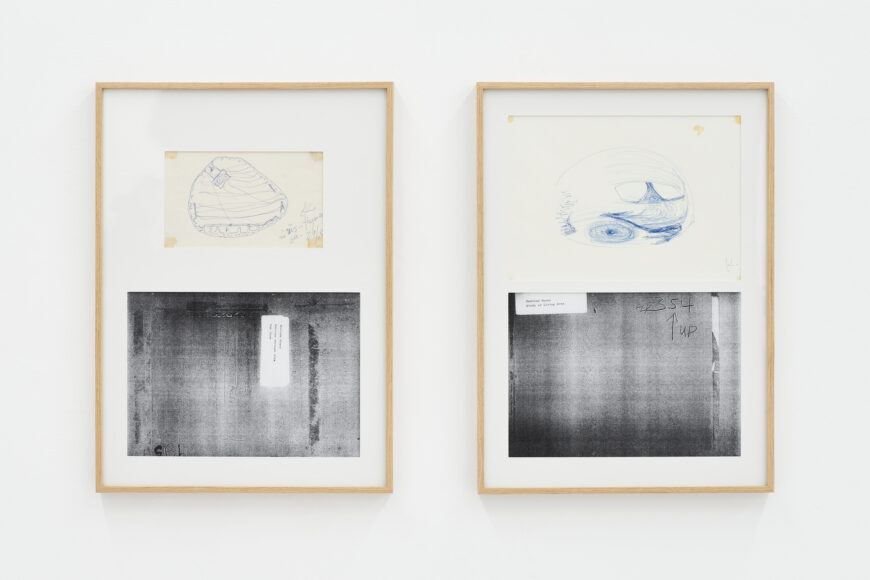

In June of the same year, Kiesler was working on the Endless House project. The preserved drawings depict an oval structure made up of a series of soft shapes. The house appears to be an organic being continuously undergoing further metamorphoses. Kiesler’s project was often viewed as a utopian idea of an organic synthesis of architectural form and function. According to this perspective, the house was supposed to reflect the life developments of its residents: their activities and relationships as well as their need for both personal and common space. Such a view, however, does little to render the numerous fundamental ambivalences inscribed in the architect’s project. A closer reading of Kiesler’s materials and texts allows for a different image of the Endless House to emerge, one that fractures this utopian vision.

Kiesler had a peculiar notion about the function that architecture played in human development. He believed that it was fear that underpinned the “construction instinct” – fear, which he understood as the primary drive for most human activity. This angle allows for a completely different view of the architect’s projects: from this perspective, Kiesler’s house resembles more of a bunker or subterranean shelter. We are looking at a space designed to give one a chance of survival. In this respect, the Endless House’s plans from the 1940s surprisingly resemble Henry Moore’s drawings created around the same time during the bombing of London, when some of its residents found shelter in the underground tunnels of the subway system. These works show figures sitting or lying down on the floor in dreary corridors deep below ground. In the case of Moore and Kiesler, architecture is simultaneously presented as a space of fear and hope for survival.

The author of the Endless House often reflected on the shape of the future. However, his prognoses were far from the optimistic visions that dominated the postwar period. The artist’s drawings do not depict airy, glazed structures that became the hallmark of that time. In his unfinished book about the history of architecture, Kiesler described a future where the human race would have to descend under the surface of the earth and revert to a system of underground caves in search of shelter from bombs and radiation. One of the drawings features a mountain which has been hollowed out in order to build a shelter. The mountain’s pinnacle reaches the outer layers of the atmosphere while its foundation is submerged in the ocean. The sun sketched on the right side appears to be consumed by a series of explosions. When the first nuclear bomb was blasted in 1945 in a desert of New Mexico, the nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer thought of a fragment from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the Mighty One.” Underneath the shelter located inside the mountain, Kiesler used a dotted line to draw an underground space captioned with a single word and question mark: “grave?”

II.

How to approach the similarities between the practice of the Austrian-American architect and the works of Piotr Łakomy?

Łakomy was born in 1983. In 1986, the accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl resulted in huge amounts of radiation spreading over large swaths of Europe and the Soviet Union. Seconds after the explosion, a phosphoric blue glow rose above the damaged reactor. It was produced by ionization – a process during which atoms achieve a higher energy level that disrupts their previous structure. There is a similar blue glow hovering over Łakomy’s works. His fragmented objects, scattered around in space, seem to be marked by a violent burst of energy which has disrupted their original structure and deprived them of their previous function. His works’ tissue, spanning between references to organic and non-organic matter, has either been damaged or undergone rapid multiplication – similarly to matter exposed to radiation.

Łakomy’s works can be viewed as a contaminated landscape, marked by a central void around which objects-sculptures gravitate. This is why they can be referred to as post-objects – material structures existing on the outskirts of a past event. This central event, which has both an individual and social dimension, has led to a gradual degradation, and subsequently, mutation of the genetic code of the entire reality. It is this process that aptly renders the nature of Łakomy’s work, where the previous boundaries between organic and artificial materials are being challenged. However, the blurring of these boundaries is not spontaneous but comes as a result of an explosive power, which triggered a reconfiguration of the pre-existing structural order.

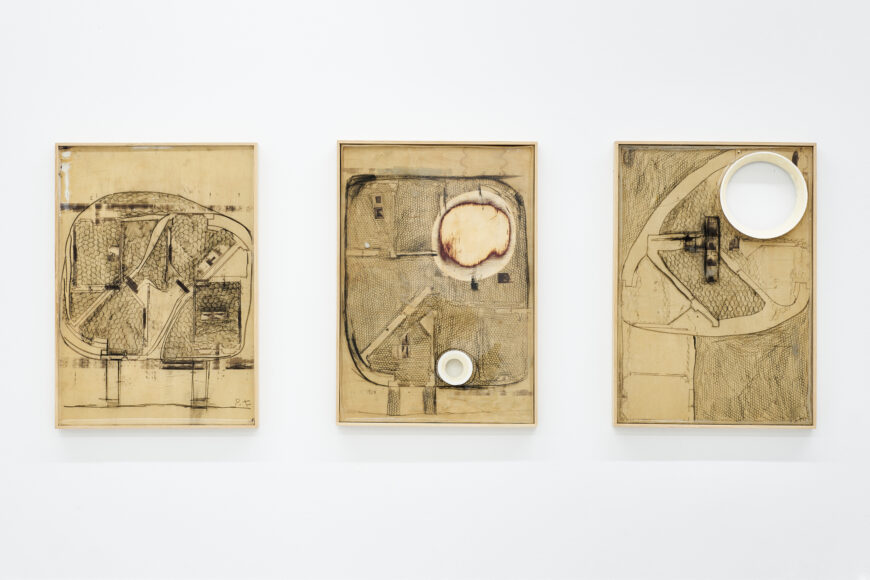

Somewhere in the background of this vast landscape stands a fractured construction of a house. In his work, Łakomy often reverts to this motif. A key thread that connects his practice with Kiesler’s project is architecture viewed as a field of interaction between humankind and the environment. This thread has resurfaced in Łakomy’s work since the beginning: he has often made references to the ideas of Le Corbusier and Adolf Loos, among others. However, the approach of the artist to the subject has recently shifted. Increasingly often, his works have included references to specific spaces of his activity: his studio and home. The artist seems to have developed an interest in mapping the dynamics of his own steps and moves. Similarly to Kiesler, these spaces have an ambivalent character: although at first they epitomize our desire for refuge, it soon turns out that they also produce a sense of anxiety and claustrophobia.

The exhibition Trough the Ribs features two objects that are a direct reference to the idea of inhabiting a specific space. These are two aluminum frames that reflect the shape of a door and a window. However, both elements are stripped of their functions; they cannot be opened or stepped through. They seem to be hanging in the void. Similarly to an ongoing mutation, a colony of ostrich eggs is spread on the door. A resin mold of a vest is affixed to the window – once stiffened, the object starts to resemble a fragment of antique armor. Ultimately, clothing is also a type of shelter; a membrane stretched over our bodies designed to filter exterior impulses. The objects featured in the exhibition resemble fragments of a “split house”, which cannot be put together into any kind of whole. No one will ever inhabit this fragmentized space.

The show will also feature a series of Kiesler’s drawings selected by Łakomy during his stay in Vienna. In one of the sketches displayed, the walls of the Endless House were drawn as parallel rib bones. Kiesler’s project reveals another meaning: it is a house of bones, an ossuarium. Ossuaria were built in the moments of great crises, when there was no room or time to organize a traditional burial. This surprising picture encourages us to look at the Endless House from yet another perspective: as an example of what the ethnographer Elizabeth Povinelli referred to as geontological thinking. This term describes a specific kind of human–environment interaction, where social reality, the landscape and our ancestors’ world overlap. A subject exists in configuration with different geological layers and the past as well as present social structures and identities. The introduction of the term geontology to describe the Endless House also allows us to make a connection to Kiesler’s interest in archeology and paleography, that is, the sciences which study the perspective of long duration and “cosmic time.”

This aspect is further reflected in a series of drawings made by Łakomy, which offer a visual analysis of the artist’s studio in relation to the plans of Kiesler’s Endless House. The drawings were made with a dark, thick, graphite line. Łakomy’s workshop is rendered as a shadowy space resembling the inside of a cave, dungeon or bunker with infinitely looping passageways, corridors and stairs leading to the additional levels. The interior of the studio appears similar to a vast network of catacombs: a multi-level, contaminated landscape filled with post-objects and structures made of bones. In this respect, the drawings resemble, both at the level of aesthetics and meaning, archeological sites: Łakomy attempts to extract (indeed, dig out might be a more adequate term) further interpretative layers both of his own space and Kiesler’s project. These works reveal a peculiar type of thinking about architecture that the two artists share: as a refuge that may unexpectedly show its other face and become an ossuarium.

III.

In one of the archival photos from the ’50s, Frederick Kiesler is sleeping on a mattress pushed against the wall in the corner of his studio in New York. The room has no windows. The space resembles an underground interior or a basement. In such darkness, the sense of an individual catastrophe transforms into a vision of a material breakdown that goes all the way down to the atomic sequence. The Endless House, which was designed during that time, became an expression of the architect’s reflections on the nature of the modernity at its individual and social levels. In Łakomy’s workshop in Poznań, new objects sprout from the floor and walls, much like forking mutations of the architectural and genetic structures. The studio’s space appears to be a labyrinth partly absorbed by organic matter. The artist paces it, moving through the Endless House, room by room, as if it were a building erected from bones, and through the ribs, he is looking out at reality.

Piotr Łakomy (born in 1983) lives and works in Poznań (Poland). He earned his degree in Fine Arts under Professor Leszek Knaflewski at the University of Zielona Góra. He has had several individual exhibitions: at the Avant-Garde Institute (Warsaw, 2019), the Futura Center for Contemporary Art (Prague, 2019), The Sunday Painter (London, 2019), Stereo Gallery (Warsaw, 2017), Labyrinth Gallery (Lublin, 2017), BWA (Zielona Góra, 205) and Arsenal Gallery (Białystok, 2012). He has been in over twenty group exhibitions, including Foundation Cartier (Paris, 2019), Noire Gallery (Milan, 2018), Contemporary Art Center (Riga, 2018), Królikarnia (Warsaw, 2017), Zachęta National Gallery of Art (Warsaw, 2015) and Museum of Modern Art (Warsaw, 2014), among others. His works have also been featured at the CASS Sculpture Foundation in West Sussex and Fahrenheit in Los Angeles. He has been nominated for the Views Award (2015) and “Polityka” Passports Award (2016).

Frederick Kiesler (1890–1965) was an architect, designer, sculptor and scenographer. After studying at the Technical University and at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, he started a collaboration with Adolf Loos. In 1923, he joined the De Stijl group at the invitation of Theo van Doesburg. In 1926, he emigrated to New York, where he helped promote avant-garde ideas: abstraction, non-figurative painting and bringing together art and everyday life. He taught at the Department of Architecture at Colombia University and was the director of the Scenography Department at the Juilliard School of Music. He was a pioneer in using film projection in the theater. In 1942, he was commissioned by Peggy Guggenheim to design The Art of This Century Gallery, where he planned every detail, including the innovative systems of exposition and lighting. In 1947, he created Salle des Superstition for the Parisian Galerie Maeght and prepared the famous Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme by Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, where Kiesler was also featured as an artist.

One of his key architectural projects was the Shrine of the Book (Heikhal HaSefer), which he designed with Armand Bartos in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. However, Kiesler’s lifework is the Endless House project, developed over the decades but never fully completed and realized.