Studenci i Studentki pracowni Izy TarasewiczAbsence of Protagonists Artistic mentor: Iza Trasewicz

05-31.07.2022

“Unhappy the land that needs heroes”

– Bertolt Brecht, The Life of Galileo (1939) sc. 13

In traditional western narratives, the reader is encouraged to identify with a singular protagonist, a hero defined by agency, free will, and psychological depth, who undergoes an evolution and resolves problems as the story progresses from beginning, middle, and end. Our world today can be characterized as one of continuous crisis and uncertainty, from the COVID pandemic to increasing environmental collapse, from war in Ukraine and elsewhere to the ongoing physical and symbolic violence brought about through the intersection of economic, geopolitical, gendered, sexual, and racial injustice. Given this crisis, there is a tendency to look for new heroes who would simply save us from the problems of today. Yet it is precisely this heroic “monomyth”, the idea that all problems are personal and they’re all solvable by a singular, dramatic individual, that has distracted us from the possibility of deeper, broader change or of holding accountable the powerful who create and benefit from the status quo and its myriad forms of harm. The artists in the exhibition Absence of Protagonists contest these simplified conceptions of identity and agency, addressing feelings of disillusionment, confusion, and disharmony to destabilize the fantasies of a singular saviour and its imbrication in the harmful myths of our contemporary era. The systems that we struggle against in the contemporary world, that MUST be struggled against, will not be brought down by a lone hero. Refusing to be seduced by toxic subjectivities and the lure of personality, these artists use a variety of media and formal strategies to make visible and confront the problems of today, and to imagine new narrative forms and ways of living and being in our time of chaos. The very absence of protagonists, antagonists, and simple plots curiously brings the individuals to the forefront, displaying the intricate complexity, mundanity, and subjectivity that make us all who we are.

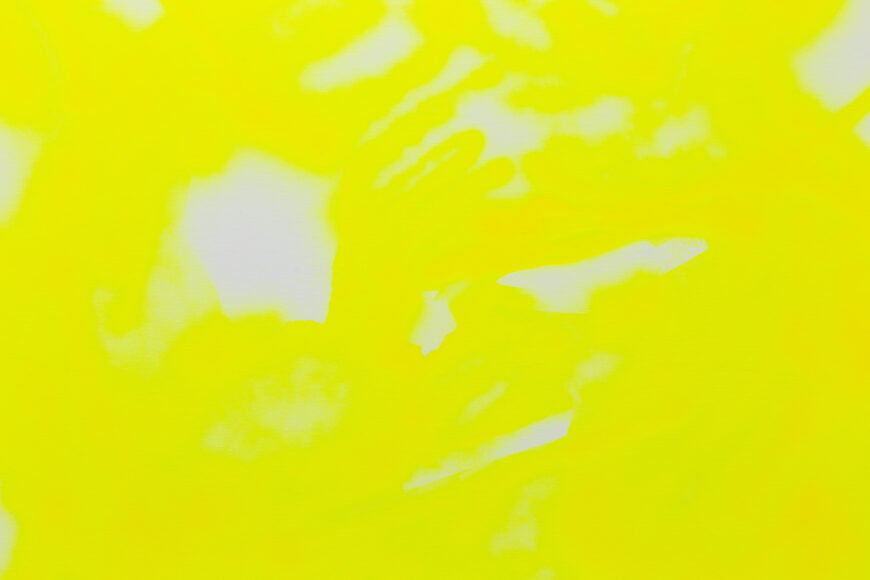

Wojtek Nika’s fluorescent neon painting Za Garażami depicts the Japanese character Pikachu, the celebrated mascot for the Pokémon entertainment franchise. With its electric powers, Pikachu is a tough, therefore prized, “pocket monster”, but with its small, yellow body, it is also cuddly and cute, serving as an icon for a “friendly” multinational capitalism. This monster is at once property and pal, capital and companion, protagonist and puppet; an avatar, but also an accessory. For the artist, the character recalls the naïve ideals and ethical simplicities of childhood, yet by enlarging and loosely rendering the figure in glowing paint, he emphasizes the toxicity of this form of heroism and artificial friendship, and calls attention to the increasingly virtualized attachments that creep into our daily lives. Pokémon’s inherent logic of acquisition (“gotta catch ‘em all”) is demonstrated as an exaggerated form of desire that comes in tandem with an enchantment of the world and commodities, which seeks to ameliorate a world of detachment and confusion through an image of intimacy and cuteness.

The intimacy of capitalism and the increasing commodification of our identities is made most visible in Laura Radzewicz’s fictional enterprise NYXEM, which parasites the data collection mechanisms of tech corporations and introduces noise into the workings of surveillance capitalism. Tracking our every move, information brokers extract our data and trade our personal lives for profit, exploiting our vulnerabilities, sensitivities, and desires. By co-opting the appearance of advertising with uncanny CGI renders and familiar yet convoluted jargon, Radzewicz’s campaign infects social media streams, merging with the content of targeted ads to introduce a counter-narrative that calls attention to the collection, commodification, and instrumentalization of the dark data of our inner lives and habits.

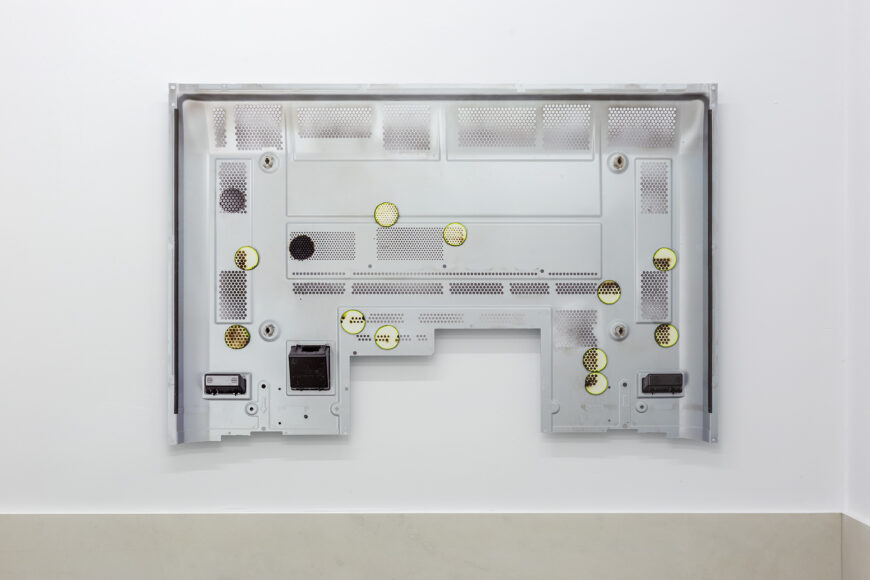

The propagation of readymade lifestyles and capitalism’s logic of waste and consumption is a core principle in the works of Miłosz Rygiel-Sańko. The artist’s sculptural assemblage exploits the ready-to-assemble standardization of particle board furniture to bring together disparate elements, yielding a “personalized” framework of home-décor whose use is ambiguous yet familiar. As a further nod to the flattening of social relations and the (mis)use of commercial objects, the artist also presents a photographic print that represents the rear side of a flat-screen video monitor overlaid with slices of zucchini with burned dots, as if the monitor had been used as a grill. Parodying the illusion that one can understand technology better by investigating its components and “back end”, the image demonstrates technology as a “black box” whose inner workings are opaque and mysterious and imagines other uses of the detritus of capitalist consumption.

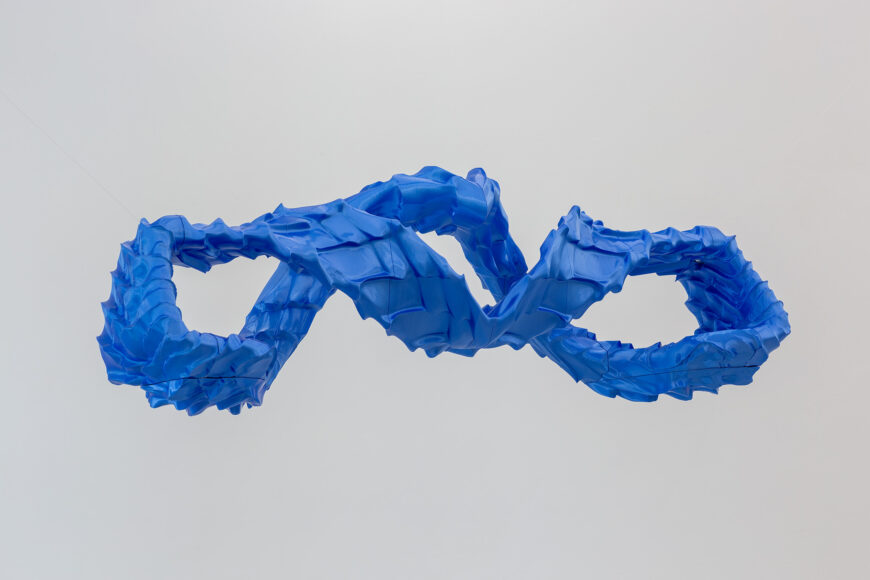

As a further critique of techno-fetishism and its role in the production of our subjectivities, Jakub Kanna’s Too Fast to Last charts a history of the modernist obsession with speed and technology through the expansion and subsequent failure of car culture. By setting Marinetti’s 1909 Futurist Manifesto in dialogue with Franco Berardi’s 2009 Post-Futurist Manifesto, the artist adds his own speculative manifesto that calls attention to the decay and destruction brought on by cars and their infrastructure. To illustrate this entropic decay, the artist produced a sculpture that contorts the form of a street racing car spoiler into a twisted mobius strip. In a clever reference to the disfigurement of time and space in our contemporary world, the 3D printed object is comprised of an entire kilometre of thermoplastic filament, which is set into contrast with the slow, laborious mechanical manufacture of the object. Thus, the slowing down of speed analysed by Berardi is embodied in the object itself, which the artist uses as a nuanced critique of the “capitalistic race” at the core of our society.

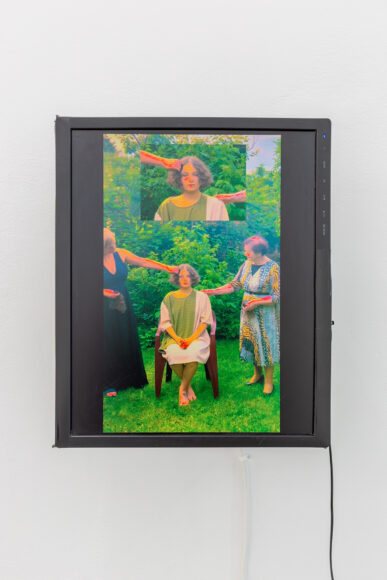

Where many of her cohorts emphasize technology as a space for critique and intervention, Julia Woronowicz instead looks to the rituals of the past as a site for a radical re-envisioning of the self. A video depicts the artist undergoing a pre-Christian ceremony from the Wielkopolska region where her long curly hair is cut to preserve spiritual power and mark her transition into adulthood. Though this tradition recalls the loss essential to any heroic narrative, her video emphasizes the social and communal dimensions of the practice and the continued repression of feminine power. Rather than discard the personal history embodied in the hair and the mystical powers of pagan practices, the artist instead fashioned the locks into an unsettling and abject pair of earrings to wear, suggesting a new female-centric myth out of ancient traditions and the possibility for spiritual power and rejuvenation in the everyday.

In both Xu Yang and Mari Ferrario’s works, they unsettle the human subject as the primary protagonist in the world by critiquing an inherent bias for anthropocentricism and human exceptionality in narratives, and therefore politics. Xu Yang’s digital collage One person, One zoo tells the story of an old man who runs a zoo by himself to expose the contradictions and possibilities in human and animal relations. As both saviour and imprisoner, the old man wants to help the animals, but is unable to do so effectively. Yet Xu’s fragmented narrative resists the urge to place this character’s story at the centre, instead giving equal importance to the experiences of the non-human subjects, and therefore envisions a more holistic and equitable interaction between species.

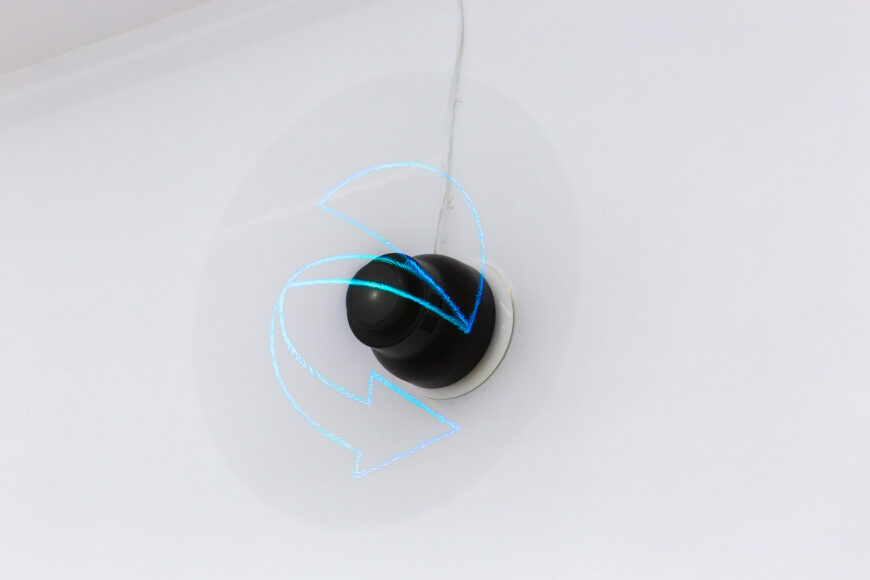

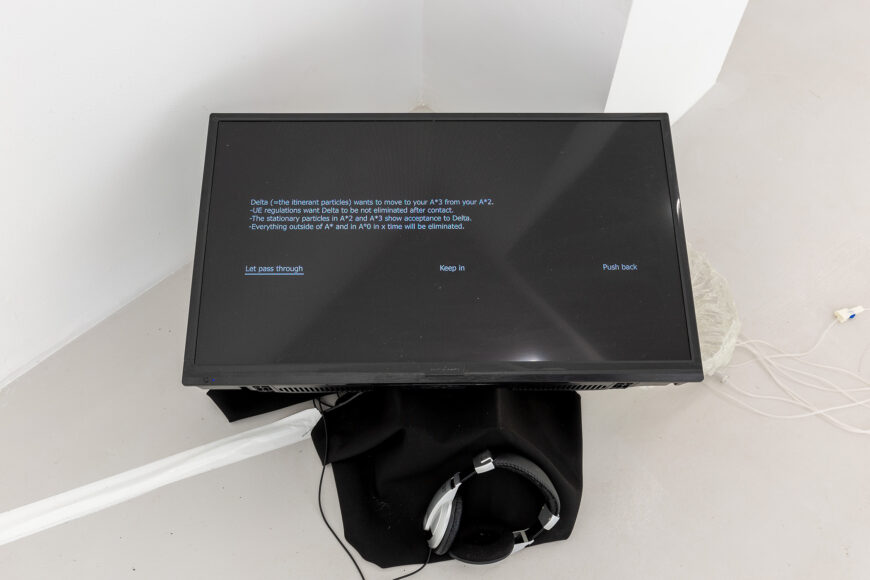

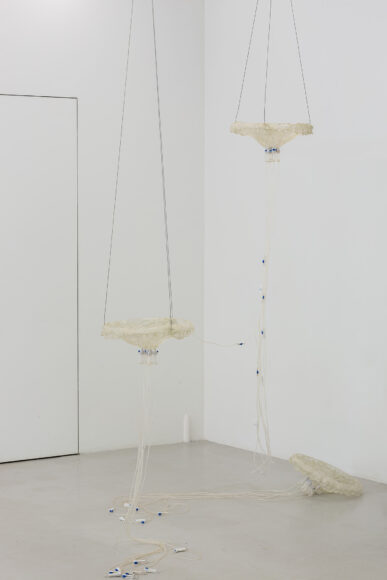

Mari Ferrario’s video installation Collaborative Task similarly decentres human subjectivity to confront the border regimes that bring extensive suffering for humans and non-humans alike. In a hypnotic video of found footage and recontextualized statements, the artist invokes rhizomic, mycelial, aquatic, and energetic flows from biological systems and suggests that these forms of connection, collaboration, and interrelation offer a model to resist the increasing division of the world. An accompanying sculptural assemblage further illustrates this principle by charting the possible flows of energy from one terrain to the next, thereby depicting relation as a bio-technical machine that functions through the enabling and arrest of movement in an endless cycle.

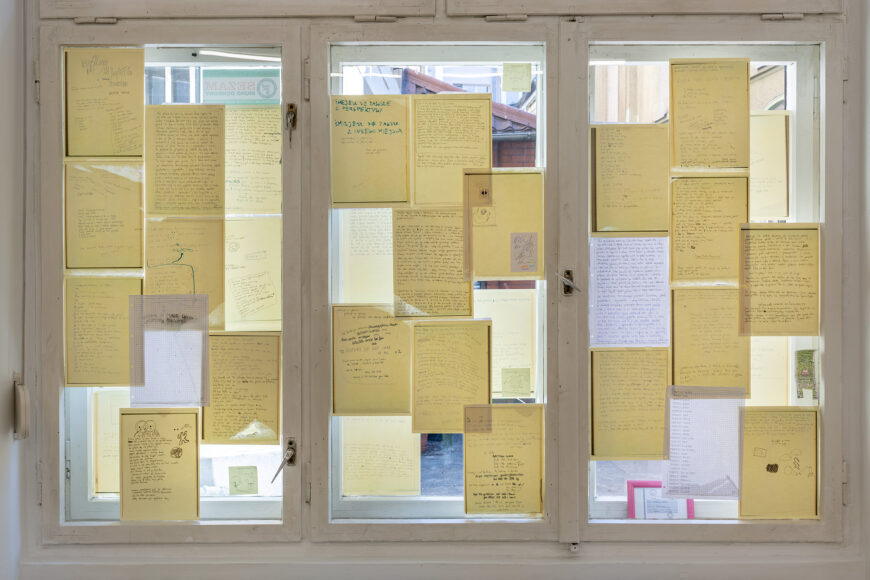

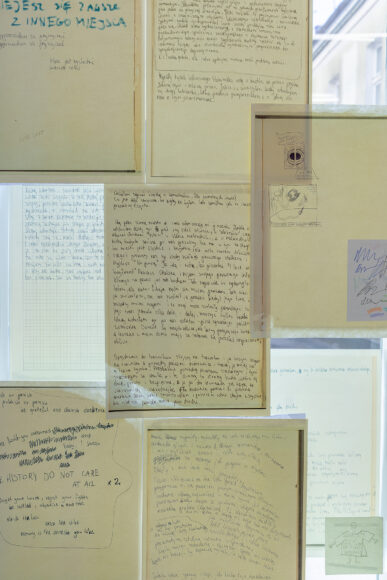

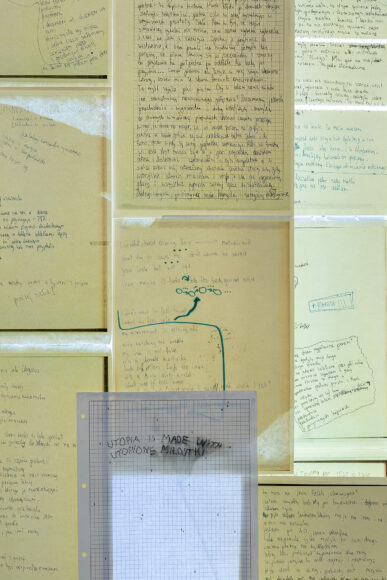

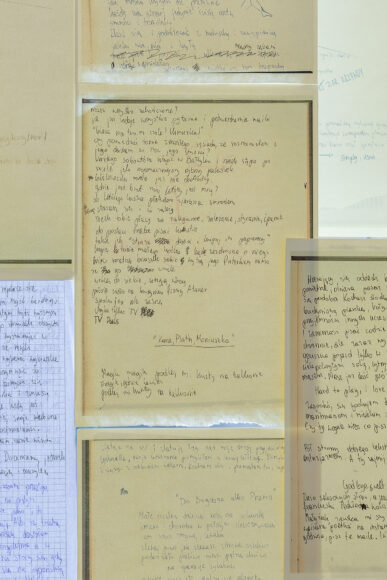

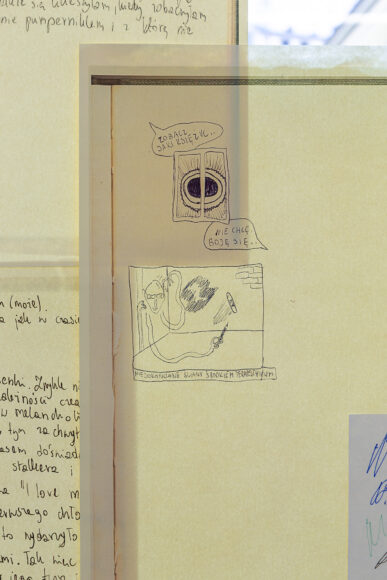

Returning to the self as a site for resistance, Julia Walkowiak’s Papierniczy, który towarzyszy mi przez życie. Papiery z ostatniego półrocza uses auto-fiction to emphasize identity as a multifaceted process of continuous becoming and reivsion where memory and fantasy are in constant negotiation. Amidst the clutter of lyrics, reflections, and found quotes, the artist keenly demonstrates Sara Ahmed’s suggestion that “memory is the amnesia you like”. By presenting her personal notes and journal in the public sphere, the artist exposes herself, while also calling attention to the ways we re-write our own experiences through imagination and manipulation. At once casual and radically vulnerable, the fragmented texts encourage identification and empathy while also contesting the image of the artist as a heroic, autonomous, and confident individual. As the artist writes: “I don’t want to feel tough” “I want support from community, I want to feel unity”.

Despite having their education fundamentally interrupted by disease, war, and all the other troubles of the world, the artists in Absence of Protagonists resist the disillusionment, apathy, and passivity that such forces encourage, charting their own means for creative growth and systemic resistance. In the presence of a certain kind of profanation of heroism, we see the everyday quality of the deed, its constant revision, its collective condition, its disruption, its unmonumental apposition. In a time of collective psychosis and confusion, the artists, each in their own ways, reject the desire for a savior and the egoism of the self, instead exploding the concept of the protagonist into a broader spectrum of interconnected relations. By analyzing the systems that threaten our survival and happiness, the artists expose narrative as an expression of power and desire and call for more nuanced and complex stories to tell and retell in our times of crisis.

– Post Brothers