Wojciech DidkowskiLOVE AND GLORY 28.04–19.05.2023

Love and Glory

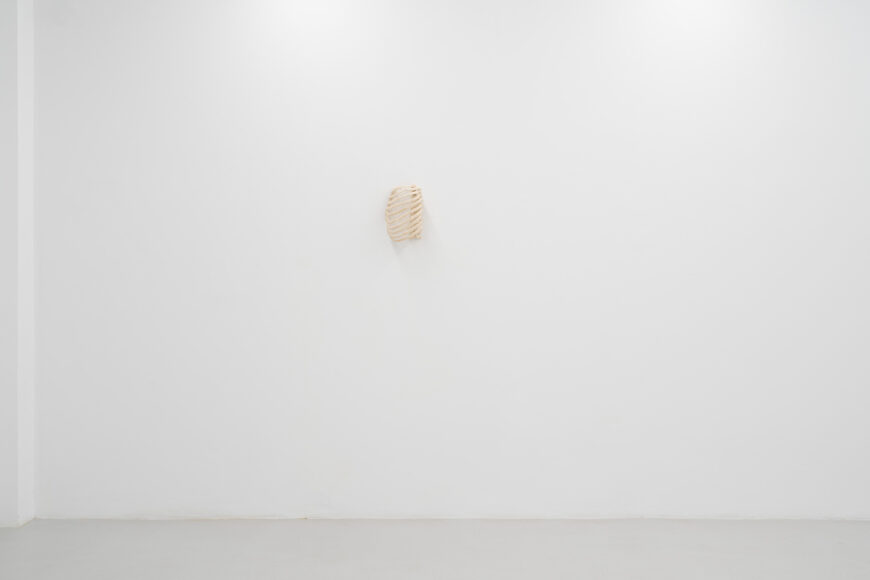

Two shirts captured at the same moment. They were fixed in an unusual form – stretched upwards, with their yokes stuffed and their backs rumpled. It was as if someone had grabbed the collar and pulled one of them over his head. What is the source of this perception? Maybe there was a need to protect the head from the rain? Maybe the sudden need to shed one’s clothes was so strong that undoing all the buttons proved too laborious? The movement was stopped at this rather than a later moment, the shirt climbed up over the darkness exposing the loins. An impression or idea of an experienced or nearly experienced situation was transformed by the power of artistic transformation into something intersubjectively communicable. Something that can now be experienced by others, that allows one to exchange insights, interpret, be seduced by the line of folds, feel the empty interior and the dust- and crystal-covered surface. The clothing fulfills its task here to some extent with excess, and in another it does not fulfill it at all – as in the Guinness Book record, when, while measuring the height of an airplane flight over the shaft of one of Poland’s mines, “no one has ever been so high while being so low at the same time.”

A shirt is not an object like any other – anyone who knows how to iron it knows this: the neckline, collar, back, fronts, cuffs, sleeves. A shirt is a complex object; a precise construction that has the physical and symbolic power to improve a person. It protects and adorns. It also used to signify membership in a social class.

Didkowski recreated the shirts in resin, with the impression of gravity, the folds of falling matter and the emptiness inside. The relationship between the man and the shirt is mutual and strong, and it is well seen in this emptiness. The shirt is a place for a living organism: an abstract place, beyond topography, GPS coordinates and any fixed embedding in time and space. A place that changes place with its owner – something more than a molt, a shed second skin, a shell. This emptiness, the unnatural absence of a human being, somewhat resembles a ghost figure from family films. The spatially limited absence, the incompleteness of the shirt shows the desire of the object itself, which needs a human body. It is similar from the other side: for the person filling the shirt is the closest object, something that most of all can be had.

The shirt only makes sense as a mutual concern: it protects the body and takes care of one’s image, but it also requires a lot of care – washing, ironing, taking a certain amount of caution not to destroy it, get it dirty, or get it squashed. The relationship with the shirt is therefore intimate and social, formal and personal. Perhaps this is why two appear in the exhibition: one black, the other transparent; one covered with salt, the other with something resembling asphalt. The crystals and dust with which the artist covered the shirts serve to mark the extreme entanglements of the object: from high abstraction and crystalline forms to down-to-earth dirty matter.

Near the shirts is another work – a kind of puke, resembling something between the head of the Loch Ness Monster and a prosthetic arm stopped in the gesture of a bodybuilder doing the so-called kettlebell. This time we are dealing with a simple device for disposing of something, managing excess. The ambiguous form is further complicated by gagging the fictitious water drain with a rag soaked in gasoline.

Didkowski creates art in a post-conceptual spirit – meaning that its materiality, aesthetic and formal qualities have equal weight with its intellectual charge. Extremely saturated with meaning, the objects carry a critical speculation on the idea of art and artistic practice. The series is arranged as a free statement revealing the tension between creation, working with matter, aesthetic reflection and

functioning in institutional and collector circuits, as well as strategies for success that encroach on artists’ private lives.

Didkowski is unable to disguise their positions and escape his ironic nature. Like a jester’s bell innate in his ribs, his art can be neither serious nor just for the sake of a joke – it must have all these qualities at once. As in Benjamin and Kosuth, “…One can also consider that a work with the right political overtones should necessarily possess all other qualities.” Ideology, political and moral should go hand in hand with aesthetic qualities. The modern playful “tactical gauntlet” turns into a knight’s gauntlet, a fight for glory and honor. Defense of the weak and dedication to a higher cause is leveled to the level of the game. And in reverse: the imitation of the voice of the excluded, the appropriation of the class struggle, the phony emancipation discourse gives the game the appearance of a noble struggle.

Once a Tumblr and now an Instagram are churning out the next generation of art dancers who are afraid of even one false step. Ideological commitment or lofty cluelessness allow them to sail confidently across the dance floors of institutions that should be shattered by a fearless desire to make mistakes. Value, right or wrong, is nowadays determined by a split-second, instantaneous fit into a set constantly updated by influential profiles. It’s difficult with every artwork you see to ask yourself a whole list of questions once posed by Dave Hickey, which let me remind you of: “How long will I remember this work, and how long will other people remember it after this exhibition closes? Does this work give more than other works? Is it better than other works in this style? Is it more interesting than the wall in front of which it stands or on which it hangs? Do I adore it, and if so, how long will I adore it? How much will I think about her? Will I miss her? How much does she surprise me? How many words could I write about her? How much could I pay for her? How much would I get rid of her for? What would I give up to have her? How many people agree with me about her? Who are these people? How complex is the constellation of other objects in which this work functions? How strong will it become in the history of art, if at all, and if so, how wide a circle of influence will it find? And finally: does this work have any significance? And does this significance have any weight?”.

The shirts are growing out of the walls, only part of them is visible. Where is the missing rest? Certainly not in the gallery. They have been removed from the art space, like Lawrence Weiner’s painted-on maxim “Far too many things to be contained in such a small box.” Perhaps the problem is not the number of things and the size of the box. Maybe the problem is the practice of fitting in itself. Wojtek Didkowski is strongly skeptical, perhaps even reluctant, about the art world, about the practices and attitudes that this world enforces. But he is also full of faith that this is not the only environment in which to deal with art. It is precisely somewhere out there that the other half of his work is to be found.

Jakub Bąk