Clemens WilhelmTHE END OF SOMETHING 9-24.11.23

Notes on THE END OF SOMETHING

It is probably the best known building in the world. It is probably the best known tourist attraction. It is 130 years old now, and it is showing a lot of rust, even when seen from a distance. Like the rest of Paris, it looks like it is part of a museum of „better times“.

When it was built for the world fair, it was the center of a colonial exhibition in which also people from all the colonies were exhibited. The built model villages of these „half-civilized“ people to demonstrate to the French people that the investments into the colonies were justified. These people were so close to being „civilized“, it would only be a matter of years before they would be as human as the French.

It is hard to imagine the normality of open racism in Europe around 1900 in hindsight. It is impossible for me to imagine life in the colonies. But this is the place, the same place, Paris, the former capital of the world, and the Champ du Mars, the field of the ancient god of War and Spring, because smart armies start war in Spring. Ad this big metal phallus, 300 m high, made out of steel, poking out of the city into the sky. It still manages to impress, and it still has a lightness and elegance to it, considering that it is just tons and tons of metal.

Today the tower is the center of the tourist world. You have not been to Paris, if you have not seen the Eiffel tower. For Non-Europeans, you have not been to Europe if you have not seen the Eiffel Tower. The significance of this tower in China is beyond my comprehension. You see it everywhere in China, it seem to signify many things, but above all it means „Europe“ and „upper class“, as well as „romantic love“. A Chinese girl once told me in China after ten minutes of meeting that she would like to go to the top of the Eiffel Tower with me. What does it mean to her? I have no way of knowing.

The tower is surrounded from morning until evening, even at night, by tourists and their technical devices. They point their cameras, phones and tablets to the tower. They come from all over the world, as far as I can see. Certainly, they are all middle and upper class, it is not cheap to be in Paris, and it is not cheap to come here. Apart from the Romanian and Pakistani men who sell beer, wine, champagne and water in their daylong singsong repetition, and the Subsaharan African men who sell cheap Chinese-made replica of the tower and other plastic gadgets such as selfie-sticks and power adaptors, everyone you see is rather well-off.

The amazing thing is that everybody, no matter which cultural background, seems to be doing the same thing. Taking pictures, of the tower, of themselves, but mostly of themselves in front of the tower. I observed some people who spent easily 2 hours posing in front of the tower. It was certainly more women than men who posed, and certainly more young women than older women. There was a big number of girls modeling there, probably for their social media accounts. It was obvious, that most of these pictures were made to be shared immediately with the world. They were looked at, liked, shared, consumed, and then forgotten at the bottom of a social media feed. Few of these pictures will really be looked at again in the future, they will be sitting on hard drives and in the data clouds, collecting dust, so to speak. The digital Alzheimer of the future might wipe them out.

Photography turns people into data. This is why smartphones had photo cameras from the beginning, and this is the feature that made them such a success and such a versatile tool. They create image data to be sold and exploited by social media platforms and Google, Amazon, Facebook, Instagram, Apple etc. These pictures are interpreted by machines, by algorithms, rather than people. Photos to be looked at by machines. What do the machines make of people posing in front of the Eiffel Tower?

Are the internet giants the slave drivers of now? Are they extracting data out of the global population like the trade companies of the past that dragged natural and human resources out of the colonies? Are we all like the aborigines who traded their valuable resources for glass beads, because they did not see the financial worth and capitalist system behind this trade? Were glass beads so different from cat videos and free email and cloud services? Are our current leaders like the corrupt local leaders of the colonies who accept the bribes by the corporations and in turn keep the population down so the companies can extract the data? Why is there „nothing that can be done“ to tax data mining?

The masses are the masses. They always have been like this, and they probably always will be. I dont believe that humans in general change very much. Evolution is very very very slow. If you look at the oldest cultural artifacts from the Ice Age, you already see that there were hierarchies, and there were groups. People have to cooperate to survive firstly, and then they are forced to cooperate to get ahead of the neighbors. Cooperation is our greatest gift, but also our greatest problem. We like to belong, it feels good and safe to be part of something bigger, to be needed, to be appreciated by others, to be part of a group. We need rituals to keep groups together, we need repetition, we need to be told what to do. Most people want to do exactly what everybody else is doing. It is understandable, it seems to be safe, and it does not create friction. If you are stuck in a group of pedestrians trying to get through a narrow doorway, the best thing to do and the fastest way to get through it is to stay in the middle, just like with running water. The people on the sides will take longer, might get hurt, and will have a varying speed compared to the ones in the middle.

An American woman asked me, when she saw my big camera on a tripod, if I knew where to take the best picture of herself and the Eiffel Tower. I tried to help and asked what she would think is „the best“. It was obvious for her: „I want the one that everybody is doing.“ I sent here up to the stairs of the Palais de Trocadero, the spot where most of the posing action is happening. She was happy and left.

Why do all people want to see the Eiffel Tower? Because all the other people want to see the Eiffel Tower. Its that simple. You have to see the Eiffel Tower. What happens when people take the picture? They know that pictures of this tower exist already, and that they can google a better one that they will ever be able to take in seconds. It cannot be that they need a record of the tower itself. But there is something to capturing the moment. It is the urge to say „I was here“. If you look at Roman ruins or at Bronze Age buildings covered in Viking graffiti in Orkney, you will see that this is nothing new, people have always had the urge to say „I was here“, and to write it on the wall. Perhaps even the individual handprint in Stone Age caves had this purpose: an individual print of a hand, like a handwriting, that proves that an individual was there, at a certain time in a certain place and as part of a group. So it is safe to assume that a picture of „me in front of the Eiffel Tower“ says „I was here“ or better, „I am here“, because nowadays it is shared and posted with a time stamp immediately.

But I think there is also something bigger going on. People sense the millions of people who have done this before, and who will come in the future and do the same thing. By doing it right now, you connect to this endless chain of people, and it connects you with a large group. It is enough to make people feel good and safe that they are part of the „group of people who have seen the Eiffel Tower“.

The act of taking the picture is a varied and complex ritual as well. It calms people somehow, it releases endorphins, and it freezes time. You step out of your everyday, you put on a mask or a face or an emotion or a pose, most people even seem to dress in the morning knowing that they will take this picture today.

This act of photography has a spiritual dimension. The act, the pose, the travel, the place & time connection, the group connection all make it very culturally complex. And of course there is also a connection to death, all photography is connected to death, as it captures the light of a moment that will only exist once, and will never come back in the same way. Photography is always looking at a moment that is gone, that is dead. When you see into the eyes of a person in a picture knowing that this person is now dead, the expression of the person changes in your perception, and it seems to look at you over the abyss of death, of time that has passed, of moments that have not been captured and remembered. Photography heightens the moment, and captures it from the endless flow of events. It is like picking up a shell on the beach, one in billions, and taking it home before the sea washes it away again.

Clemens Wilhelm

YOU CHILDREN WILL LEARN TO LIVE THERE

How to raise your children to inhabit a world that will look radically different from what you know? Should you embrace technology, and apply the logic of data mining to your own self? How much self-reflection and how much sharing is still healthy? How do the algorithms of big internet corporations steer your wants and needs, and how did we come to this new form of digital existence in the last decades? How do you argue with nature in the face of the climate catastrophe, or are we just doomed? At which point should you stop calling it a crisis and start calling it a collapse?

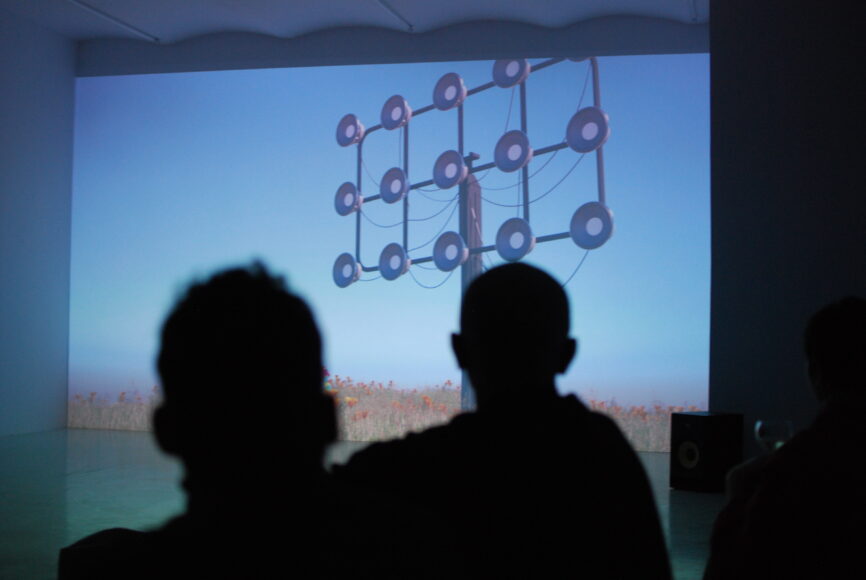

This video program brings together four artists who think deeply about these issues and address these questions, and many more. A sense of uncanny premonitions and impending doom runs through these works. The grasp of technology on our lives and the effects of data extraction tools become tangible.

The concepts of the private and the public have severely shifted. Where does my “self” end and where does “the outside” start? Are we a part of “nature”, or are we opposed to it and want to exist removed from it?

Is the extinction of humans inevitable if we keep destroying our habitable zone on this planet? Is data the new oil? Am I a mine? Is technology the “death of mankind” or is it our “only hope” for survival?

We may not find out the answers but – as the uncanny narrator of John Butler’s “Children of the Null” reminds us – “you children will learn how to live there”.

THE TOURIST AND THE LOSS OF THE REAL

“In ‘The Tourist and the Loss of the Real,’ artist Clemens Wilhelm takes us on a captivating cinematic journey through a world where reality blurs into hyperreality and authentic experiences become simulacra.

The journey begins in Iceland, where a white naked man finds himself immersed in the vast landscapes, blurring the lines between romanticism, tourism, fetishism, performance art, and elements of pornography. This evocative visual experience juxtaposes elements of the pornographic with the aesthetics of National Geographic and the contemplative allure of Caspar David Friedrich, creating an intriguing tension between absurdity and beauty.

We then find ourselves in the Czech Republic, where a man and a woman, who initially connect online, attempt to bridge the gap between their virtual personas and real-life encounters. However, their quest for genuine connection is hindered by substitutes and mediated technology, all under the watchful eye of a computer camera. Their dialogue, fixated on the beauty of Prague, raises questions about the nature of authenticity in our increasingly digital interactions, highlighting Baudrillard’s ideas about the proliferation of simulations and the dissolution of the real.

Our journey continues to China’s ‘Window of the World’ Entertainment Park in Shenzhen, a place that houses 140 imitations of the world’s most iconic tourist attractions . In ‘Simulacra,’ Wilhelm takes us on a tour through this theme park, where replicas of the Gizeh Pyramids, Stonehenge, and even the Statue of Liberty, among others, stand as miniature facsimiles of the originals. Yet, the towering replica of the Eiffel Tower overshadows them all, prompting us to ponder the meaning of these iconic landmarks when removed from their original contexts and placed in an environment of hyperreality.

Lastly, we find ourselves in Berlin, where Clemens Wilhelm embarked on a unique social experiment. In an attempt to become a Berlin tourist attraction himself, he sat before the Berlin Wall for two months with a sign that declared him ‘The Most Photographed Man in Berlin.’ The performance went viral, with over 10,000 photos posted on Facebook and more than 250,000 people witnessing this extraordinary endeavor. ‘ This experiment challenges the boundary between reality and the simulated, echoing Baudrillard’s ideas about the blurring of these lines in a society dominated by media and technology.

In this captivating exploration, ‘The Tourist and the Loss of the Real’ prompts us to reevaluate our perception of authenticity and to question the impact of hyperreality and simulacra on our contemporary experiences and interactions.”