Krzysztof MętelNobody is standing, everybody is standing 8–29.04.2022

The NOBODY IS STANDING, EVERYBODY IS STANDING exhibition presents the process of shaping what is shapeless; of restoring meaning to what is useless; the merging of what is falling apart. In his latest series of works, Krzysztof Mętel looks at the lastingness, disappearance and transformation of matter in relation to the medium of the painting. Using old, discarded or unsuccessful canvases – both his own and those donated by people around him – the artist recomposes them, interfering with their material layer, destroying their existing integrity.

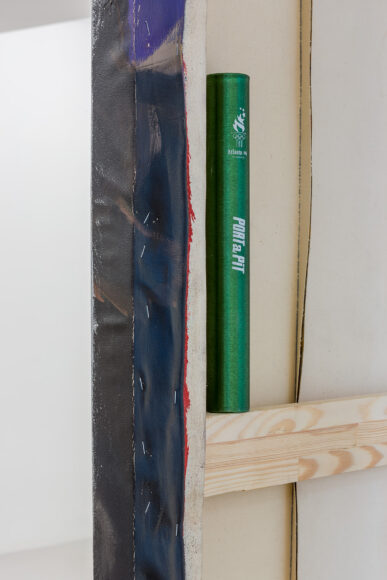

Krzysztof Mętel’s paintings are created as a result of montage. This practice means both the necessity of making a selection of the desired motifs or fragments, and inserting them into a new perspective imposed by the artist, subordinated to his ideas about the final form of the given work. His creative practice is not only about re- and over-painting. It is also about dealing with the matter of old canvases – their unfolding, cutting, touching, straightening, sewing and stretching them onto new stretchers. And so – for example – the work Untitled (3), originally with a rectangular format, gained an oval shape, and the effort in the area of the painting layer was reduced to one strong gesture, albeit one that did not completely obscure the original composition. In another work, for example Untitled (6), the artist’s interest and the intensification of changes were concentrated primarily in the area of painting and colour compositions, and the transformation meant the need to tame the expressive identity of the images used in this work. In Untitled (2), the original anatomical motifs (fragments of arms, legs) were rearranged in such a way that they became merely abstract surfaces of colour, the genesis of which was obliterated in the process of their transformation. Sometimes this struggle arises, however, from humble observation and following the nature and scope of changes suggested by the images themselves – the cut-out fragments adjust to each other intuitively and suggest new systems and connections.

Krzysztof Mętel’s painting becomes a process of establishing relationships and new hierarchies. In its genesis, it is sometimes transparent – not too tightly stretched, curling at the edges of the canvas, undulating surfaces, folds or provisionally attached corners give clues as to its history and the status of its recycled origin. They also remind us that the painting is a materiality, the mastery of which requires invisible toil and physical effort, undertaken in the quiet of a studio. These elements also suggest that for Krzysztof Mętel, the image is not so much content as a visual fact that crystallises at the intersection of painting elements such as colour, composition and format. The artist understands this type of activity is related to (de)constructing, recontextualising and rebuilding as stabilising the hitherto compositional or material instability of images. The new architecture of these works built by the artist is an attempt to support what, in his opinion, is sliding and moving.

This sense of instability in relation to images brings to mind the aspirations of architects and engineers to master the laws of statics and erect buildings that resist the process of sliding matter. The history of the Edmund Szyc Stadium in Poznań tells us about such a struggle. Built in 1929 for the General National Exhibition, it had to be closed just a few hours after opening due to subsidence of the structure and the instability of the scaffolding supporting the reinforced concrete elements. Attempts to stabilise this building undertaken in subsequent years were unsuccessful, which resulted in the need to partially dismantle the building and rebuild it based on new plans. Currently derelict and unused for years, the stadium is in a phase of decay – both in terms of matter and meaning. Until recently, what made it possible to preserve the remnants of sense of these structures falling into oblivion were the everyday spatial practices of homeless people, living, and thus enlivening, the remains of the adjacent changing room building. Although the Edmund Szyc Stadium in Poznań provokes questions and opens topics far from those to which Krzysztof Mętel devoted his attention in his latest series of works, the history and the present of the building suggest an analogy with the operationalisation of what is dysfunctional. In the case of Krzysztof Mętel’s work, this means stabilising painting. It takes place not so much at the narrative level, but at the level of means specific to painting, such as defining the format, building a composition, stretching canvas on a stretcher. These are exercises in building relationships – though not only intra-image ones.

Małgorzata Anna Jędrzejczyk

Translation: Aleksandra Sokalska-Bennett